Table of Contents

As per Scientific American in mid 2024, at least 60 000 scientific papers were written using large language models. That number is not any lower today, and the existing screening processes and peer-review cannot catch all errors and issues that result.

Publishing fraudulent data is grounds for disciplinary action and loss of trust for the individual researcher, but publishers, universities, and governments have created massive incentives for junk science to flourish a long time ago, supposedly in the name of efficiency.

Scientists love LLMs

It’s become quite difficult to find people in academia who have never used large language models in their work, be it in STEM, social sciences, or the humanities. The stereotypical image of someone in a white labcoat handling expensive equipment at a workbench reflects only a small portion of a researcher’s job, and only in certain fields.

Much of a workday for any researcher involves a lot of reading, a lot of writing, and quite a few slideshows. Given this is the case, people in the profession have usually embraced LLMs with little resistance.

Some AI tools, like GPT 4-based Consensus, offer services specifically tailored to help in these somewhat menial tasks, by searching papers from natural language queries rather than keywords, and synthesizing pages of repetitive (and somewhat sloppy) scientific writing into more succinct snippets.

AI-generated images are used left, right, and center in posters and presentations, especially by older professors. This should also be unsurprising, considering specialized tools for field-specific vector graphics can have pretty hefty subscriptions (Biorender, for instance, starts from $35 a month), let alone professional illustrators.

Then there’s the linguistic barrier. English is the language of research, but it’s not necessarily the language of researchers. Until a few years ago, it was quite common to have someone from the lab who was more fluent in English proofread manuscripts for the whole team. Now, drafts can be passed through a chatbot for rephrasing or even translating from the author’s mothertongue.

Depending on how lazy or how desperate the user is, they might just give the dataset and a brief description of the experiment and let the model write for them altogether. In the end, less than stellar results are not a concern, since the author’s writing might not be any better. Besides, no one is going to read the fine print anyway; they’re going to have an LLM summarize it to them.

Then there’s the grotesque and absurd. While there’s been no shortage of either, the most famous example came from a paper discussing intra-cellular communication in sperm cells, which included some ludicrous illustrations made with Midjourney.

The pictures are supposed to represent the methods and findings of the studies, an impossible task given stable diffusion algorithms’ inability to write text at that point in time, and by the general confusion and nonsensical nature of the representations.

Of course, the real reason for the fame of this article is found in Figure 1, featuring a vigil dissected mouse, with an anatomically improbable phallus (we can be sure it’s a phallus since the figure is illustrating how cell cultures were from rat testes).

The paper quickly did the rounds over on Twitter/X and got retracted a few days after publication. The retraction note makes no mention of the actual text of the paper–only of the AI illustrations–so it’s unclear whether the findings and data were legitimate or not. Regardless, the authors never published again in the same journal, or possibly in general.

Following publication, concerns were raised regarding the nature of its AI-generated figures. The article does not meet the standards of editorial and scientific rigor for Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology; therefore, the article has been retracted.

While it’s tempting to laugh incidents like this one off as malice or laziness, and to see the quick retraction as good quality control, the issue is much more systemic than it appears to the general audience. While LLMs and AI picture generation are exacerbating the problems with junk papers and junk data, there are incentives and issues that have their origin in the nitty-gritty details of researchers’ careers.

How science is made

Every professor, PhD student, post-doc, and researcher, virtually without exception, knows what publish or perish means. It’s not a new idiom; it can be traced back almost a century, but it still applies to various degrees in all segments of academia and private research.

Simply put, there are more butts than chairs in both universities and institutes. When a researcher seeks a grant or a job, their work needs to be evaluated somehow, and the only competent people are often the candidate’s own colleagues. In the interest of impartiality, governments, universities, and funders have adopted a number of objective measurements of the performance of their researchers, based mainly on the number of publications and the number of citations.

The rationale behind these metrics is pretty straightforward: if a researcher is a worker who produces knowledge, in the form of scientific papers, then their productivity is measured by how many papers they can churn out; and if the papers are of any quality at all, someone is going to cite them in their own work.

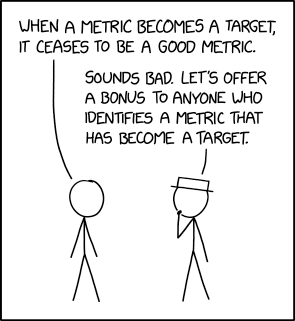

As stated in Goodhart’s law ‒ and excellently illustrated by autistic researchers’ darling xkcd‒ whenever a metric becomes a target, it stops being a good metric. Indeed, the system has grown so full of exploitsthat the target has been divorced entirely from quality.

Back when academia was a close-knitted circle of a few privileged individuals, scientific articles were a tool for scientists to reach their colleagues and inform them of their findings before those would appear in a book. University libraries would buy journals for the benefit of their students and researchers, who would find papers describing the discovery of a phenomenon coherently and exhaustively, from beginning to end.

Salami-slicing is the exact opposite, and it’s omnipresent. Since researchers are incentivized to publish more, and resources stay the same (or more commonly get reduced), the work and expense that would have yielded one comprehensive manuscript gets spread to several, each one fastidiously specific. The salami is still the same, but it needs to be sliced thinner, or else.

So the study of a particular gene in cancer cells could be divided into one paper for testing treatment A, one paper for testing B and C, and to compare them to the previous article, one to establish the role of that gene and its interactions in vitro, one in an animal model, one for comparing different populations, and finally a review or meta-analysis so the undergrad has a publication in their portfolio too.

Not only are these all counted separately, but they’re also going to be cited separately when other teams discuss the topic. The result is that only the final review traces a coherent narrative that makes the topic actually understandable.

Maybe more famously, the pressure to publish or perish is the main drive behind the replication crisis, where around one-third of scientific findings (especially in psychology and medicine) could not be verified independently. Non-significant results are uninteresting, uninteresting papers don’t get published, and that’s not an option for some, so the scientific method will need to be adjusted accordingly. Several safeguards have been put in place since the issue started receiving attention, but junk science does not come solely from inside the lab.

Publishers are actually evil

Outside of misguided administrators and overworked scientists, someone is actually making a lot of money from this whole situation. Scientific publishing is dominated by an oligopoly of a few, extremely profitable companies running the market, namely Elsevier, Springer Nature, Wiley-Blackwell, Taylor & Francis, and Sage Publishing.

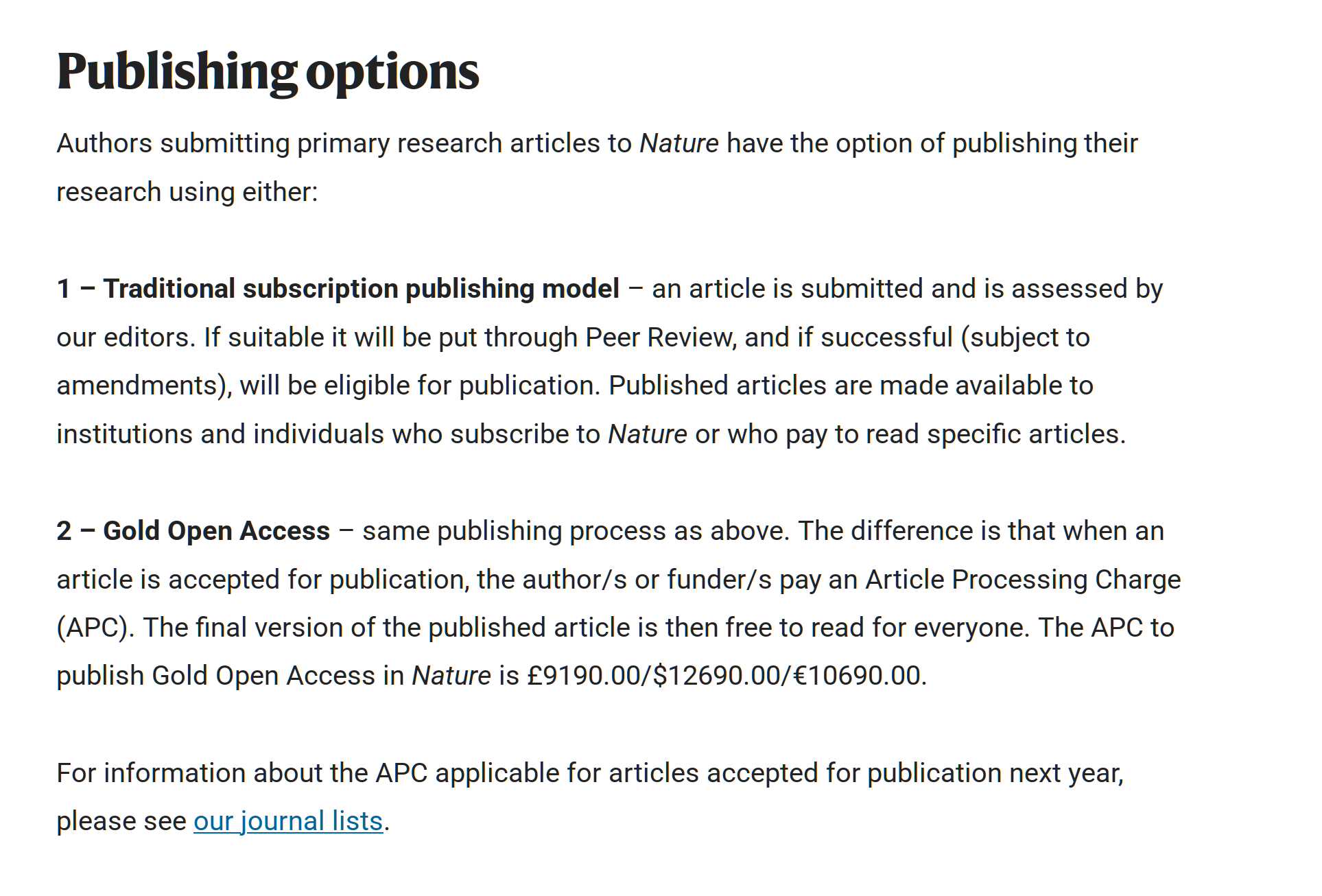

While in journalism authors get paid for the articles they write, in scientific publishing, researchers (or, usually, universities) have to pay journals fees for reviewing, publishing, and for open access. If the author chooses not to pay the latter, readers will have to pay to access the article, which greatly reduces its chances of being read or cited.

Most journals will ask between two and six thousand euros for open access, and elite publications like Nature put their pricetag over the ten thousand euros mark. It’s common for half the budget of a given research project to be spent on publishing fees.

In this ecosystem, the bottom feeders are so called predatory journals, which will take any manuscript that’s sent their way with almost no checks, for sometimes exorbitant prices. This is often an option for quacks and snake oil salesmen to get some semblance of credibility, but they mostly target legitimate research.

There are several tools used to distinguish legitimate publishers from predatory ones, the most established one being the impact factor and its derivatives, but they also end up reinforcing the pre-existing oligopoly, and they have their fair share of criticisms about efficacy as well.

To be clear, said traditional publications, with their huge market share and resources, are no guarantee of quality either. The paper with the surreal priapic rat was published in a journal of the Frontiers Media group, which is generally well trusted.

While the retraction was indeed expeditious, the paper had to wait 40 days for quality control, usually involving experts screening and peer-review. It’s worth mentioning that despite the astronomical fees, peer-reviewers are usually unpaid volunteers.

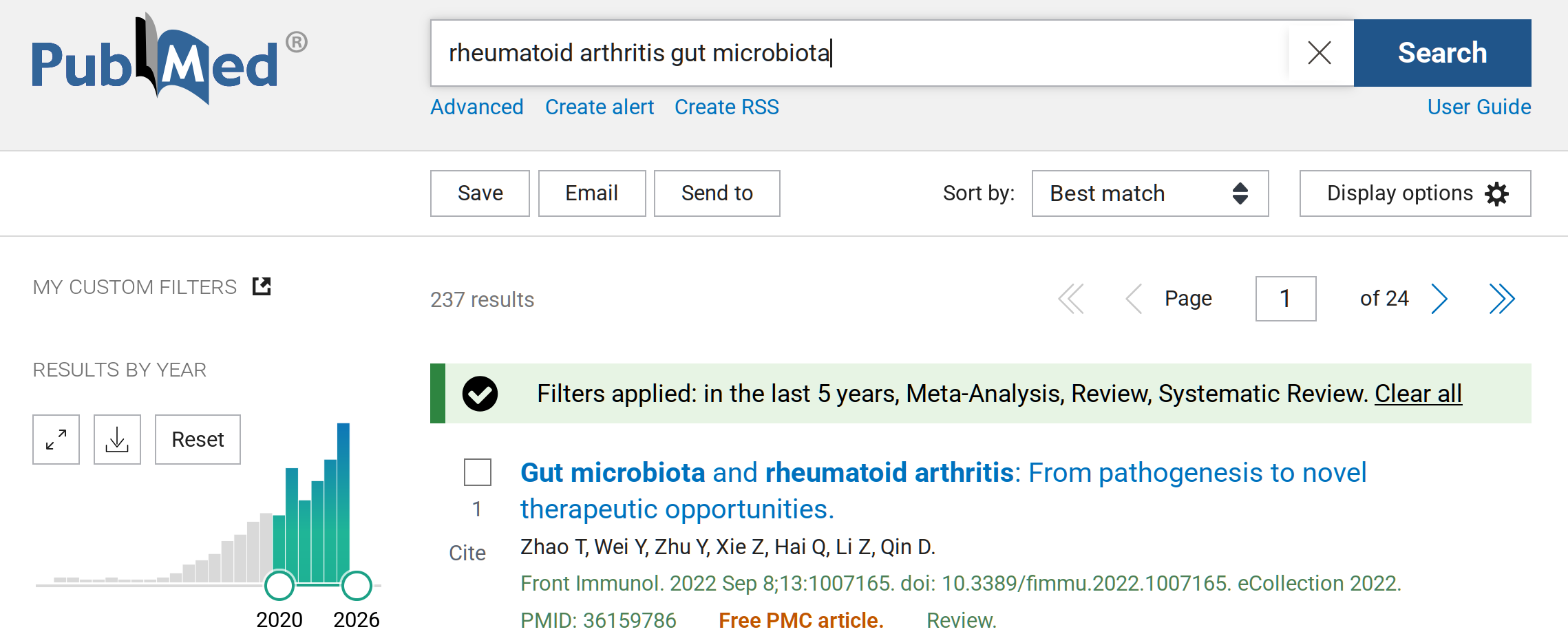

Soliciting the submission of literature reviews is also a typical predatory tactic, common to all publishers regardless of their business model. Since reviews are written by synthesizing pre-existing articles, LLMs are particularly fit to produce them quickly and summarily. With particularly glamorous or trending topics, this can end up bloating the scientific literature significantly.

For one example, by querying the search phrase “rheumatoid arthritis gut microbiota” in the aggregator PubMed, and restricting the search to the last 5 years, 558 results come out; out of those, 237 are reviews or meta-analyses. Gaining the attention of publishers (and pharma companies) has led to the specialized literature on the topic getting clogged, with almost half of the published material being redundant descriptions of the remaining half, the actual data.

Scientists have been pushing back against these toxic incentives in their own ways. It bears pointing out that most researchers have a genuine passion for their field, so they’re largely dissatisfied even with mechanisms that they could accommodate without losing money.

A particularly noteworthy and mainly grassroots initiative is the open data movement, which promotes and pursues the frequent publication of datasets from experiments in a free and standardized way. This model allows scientists to share findings quickly, to make them available for scrutiny and for new research, while also reducing time and money spent on traditional publishing. It goes without saying that the movement assumes a strong FOSS philosophy.

China and India are no different, they’re just huge

One last factor in understanding the explosion in junk science comes from the emergence of China and India as scientific powerhouses. To prehempt any confusion, their rise to prominence has been a net positive for science and humanity.

China is contributing immensely to engineering and medicine, and the idea most people have of Chinese innovation tends to reflect this somewhat faithfully. India, as well as Pakistan, while usually underestimated in general culture, are in the peculiar position of having significant resources for research while large percentages of their populations are nonetheless dealing with poor people’s issues; for this reason, they have both become main contributors in diagnosing and treating diseases like tuberculosis and leprosy, which still pose a potential risk for global health.

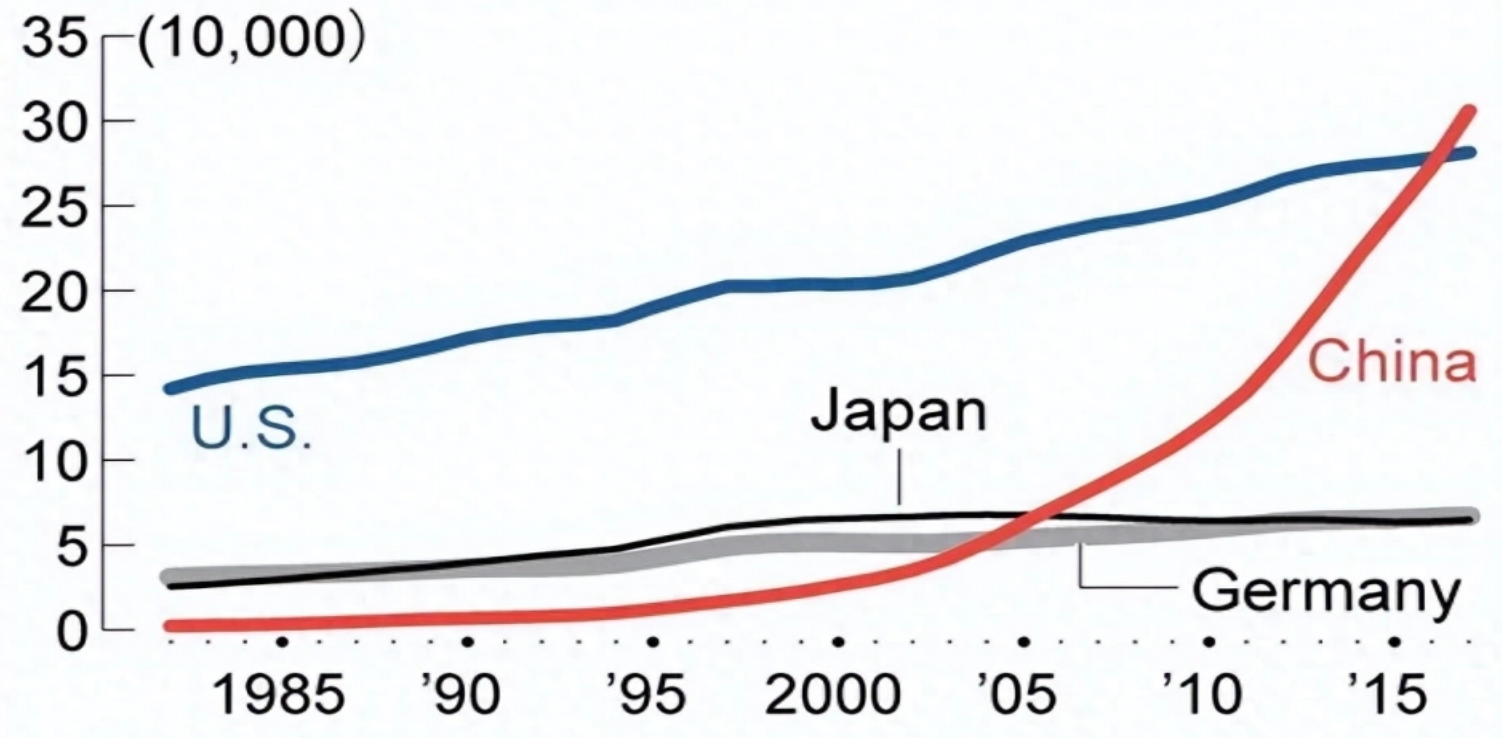

To get the scope of their role across, up to the 1990s Chinese scientists were publishing a negligible amount of papers. In the last ten years, their output has outgrown that of the United States, historically the most prolific source of scientific literature.

China itself has adopted this sort of metric wholeheartedly and pushes its students and researchers to publish more and more often, promising better career opportunities based on similar objective measurements. In other words, China is adopting the same quantity-over-quality strategies that everyone else has been using, if only slightly more aggressively, and India is close behind.

The language barrier also hit these countries particularly hard. Lots of Chinese researchers have little proficiency in English. Their Deshi colleagues are usually more proficient, though they might only be comfortable with their specific dialect of English and deem it unsuited for academic writing, due to cultural associations. Academic English is a different dialect in its own right, heavily influenced by foreign syntax and specific jargon, but it’s considerably closer to some British and American dialects than it is to those of India and Pakistan.

Given the huge population of China and India, the institutionalized push for larger outputs, the specific needs of Chinese and Indian researchers themselves, and that academia is still a valuable path to social mobility in some contexts within both countries, it’s easy to imagine what the effect may be.

The sheer volume of publications from these countries is such that any percentage of junk will be a lot of junk, and AI has been particularly effective in expediting its production, in Asia and everywhere else.

Large language cannibals

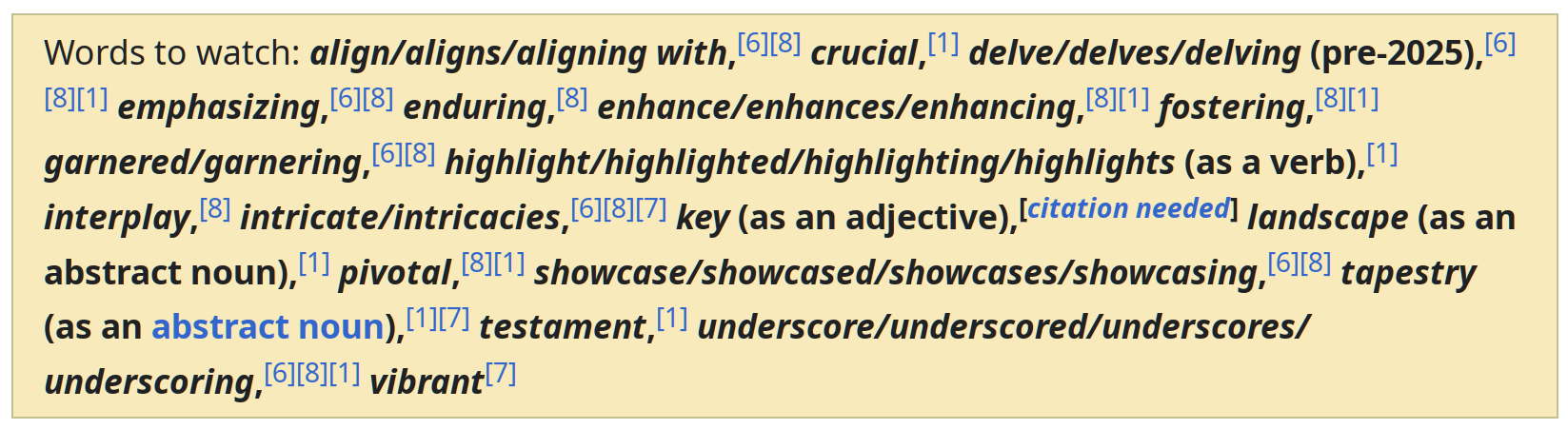

GPT, along with several other models, was initially trained on scientific papers. Indeed, various early quirks of “AI speak” are inherited directly from academic language: impersonality, the use of long, uncommon words of Latin origin instead of their Anglo-Saxon counterparts, lists, and over-enthusiastic tones are all very common in STEM papers.

So if LLMs are trained on scientific literature and a growing percentage of scientific papers is written with LLMs, it’s fair to question what consequences may ensue. We can take one clue from stable diffusion models when they started using AI-generated pictures in their training dataset, which led to the emergence of a loosely defined “AI style” in subsequent output.

Even the yellow tint that became infamous in the last year and never really went away is often attributed to the models recycling their own products, particularly those imitating anime by Studio Ghibli.

It’s not a given how this will translate to text output, but the repetition and consolidation of bias is on everyone’s mind as a real danger to research. Science, after all, is supposed to be built on the correction of previous errors. It’s also unclear what filters and quality checks can be instituted, if effectively detecting AI is even feasible, and if publishers are actually interested.

As it’s hopefully apparent, the rot comes from way upstream, and AI was only allowed to fester by an environment of perverse incentives.