Table of Contents

The current Linux desktop landscape is very complex and variegated. This is a known fact about the Linux ecosystem: unlike commercial desktop alternatives, you do not just get one target. There exist many desktop environments, at least as many software distributions, and, as if that was not enough, there are several, very different ways to install applications.

This last point is the most crucial part. Long gone are the days when the only way one would install an application on a Linux system was through the distribution's package manager: nowadays, sandboxed environments are the norm.

It has gotten a lot more common to install applications using containerized environments, such as Flatpak or Snap. As we know, this approach gives us a plethora of benefits, the most important being the ability to compile an application against one single, unified runtime, and be sure it runs on any Linux system it is thrown at, no matter how the system is configured, or how old the packages shipped in it are.

It would be natural to ask ourselves: how do applications manage to work so well across such a diverse range of configurations? The answer is, thanks to Freedesktop Portals.

Thinking with Portals

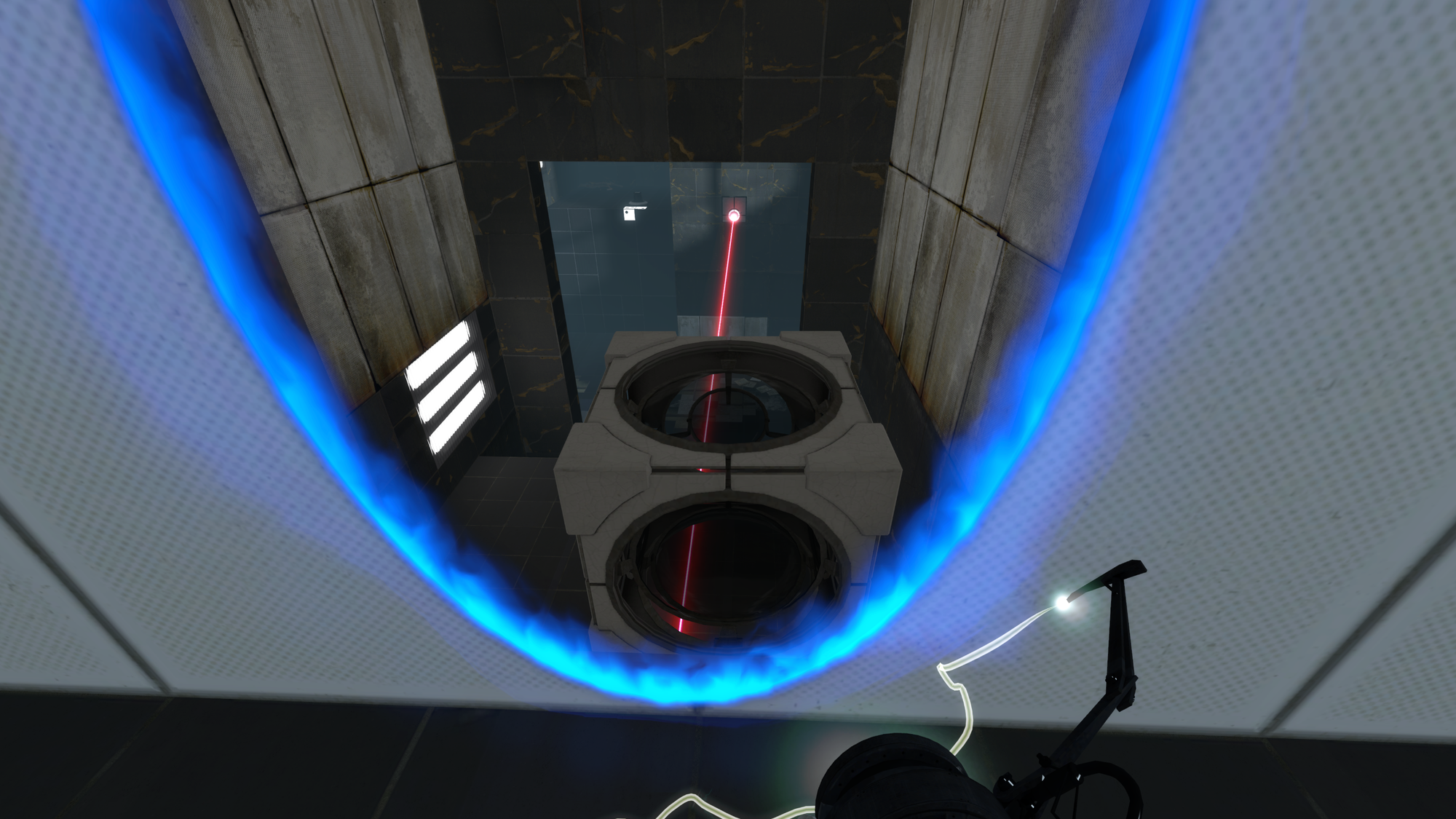

Portal is probably one of the most memorable PC game franchises to ever have existed. Developed by Valve, it consists of two titles - Portal and Portal 2 - where the player is tasked with completing a sequence of test chambers by completing increasingly intricate puzzles. While the puzzles themselves can prove pretty head-scratching, the rules of the game are quite simple, and the main part of how they are solved revolves around using your Portal Gun to shoot two interconnected portals around the chambers, and using them at their best to interact with the rest of the world. The solutions to these puzzles are often quite crafty, and it's fun to go through them. However, being able to clear these challenges solely depends on abandoning your usual intuition on how you would solve a problem and, instead, think about how portals could be useful to you in that situation. In the Portal community, we call this mindset shift “thinking with Portals”. It's hard at first, but everything makes sense once you start thinking with portals.

Linux desktop application development sort of hinges on the same concept.

First, let's make it simple. Imagine a running process, associated to an application, that seeks to record your screen. The peculiarity of an application like this is that it does not exist on its own, it needs to consume a resource to do its job - in this case, it needs to access a stream of what is happening on your monitor, then save its state for several times a second, then stitch all of those screen captures together into a smooth video. This is UNIX, so, let us suppose that you would probe a file to do this.

This would clearly be problematic. Firstly, if this was possible, it would be a giant security flaw: imagine any process running unprivileged was able to just look at your screen. It would be extremely simple to make spyware go unnoticed! Secondly, it would not work on all configurations. GNOME's Mutter compositor would handle its monitor output one way, KDE's KWin would do it another way, wlroots would choose a different way entirely. Plus, how would you go about accessing it through a sandbox, that likely shields your process from poking around with files outside its own private directory?

This is why it was necessary to come up with a standard. Applications need a standardized way to talk to each other to share resources, send each other messages and do what they need to do, complying to a standard. This need is fulfilled by dbus, the most basic layer of the architecture, we are looking at today.

D-Bus: a message bus for the Linux desktop

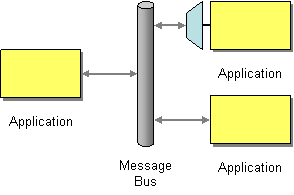

In any software system, different components usually require a shared “pipeline” to talk to each other. The broader topic of processes talking to each other is called IPC - which stands for “Inter-Process Communication”. There are several IPC interfaces available, all with their pros and cons: shared memory, mailboxes, message queues, message buses…

When you are dealing with complex architectures, made up of several components that might all need to interact with one another in ways so complex that it is pointless to try to restrain that communication to a predefined route, one of the best bets you have is to use a message bus. Every IPC interface can be thought of as something physical. You can think of a message bus as a bulletin board: it's placed in a public location, and anyone can attach post-it notes to it, or read existing post-its.

A message bus shares the same idea. Students who go read the bulletin board are the processes that subscribe to the bulletin board, while landlords advertising their laughably above-market rate double rooms located right in the middle of nowhere are the processes that send messages to the bus. This way, a process can put up a post-it (a message) that other processes who are looking at the board (subscribing to the bus) can read.

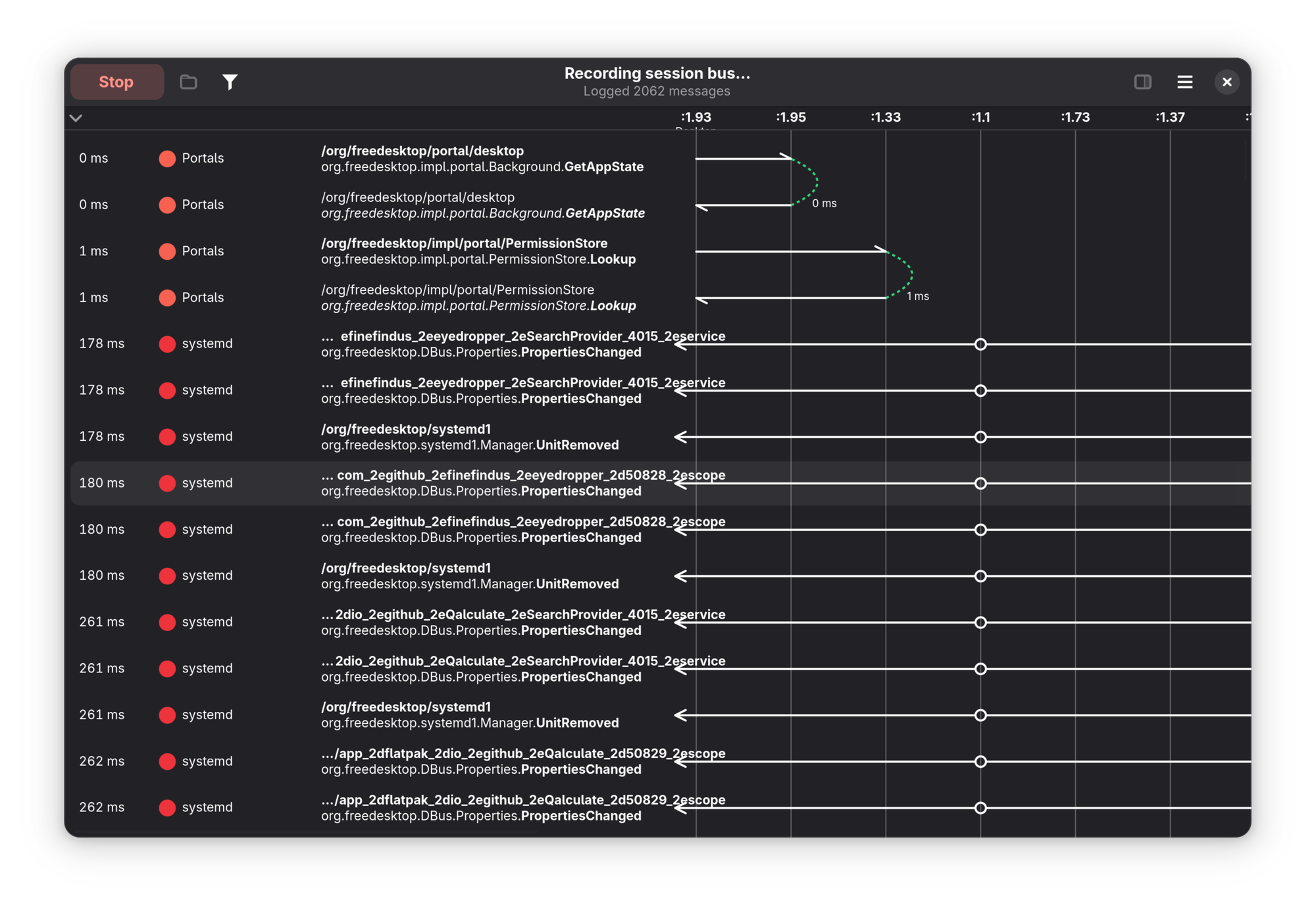

Well, dbus is the standardized message bus that applications, compositors, entities on Linux use to talk to each other. If you are curious, knowing how a message bus works, you can go ahead and see everything that is going on there. You can even get a pretty graphical overview of it using something like Bustle.

dbus all the timeSo, finally, what's a portal?

Finally, what is a Portal?

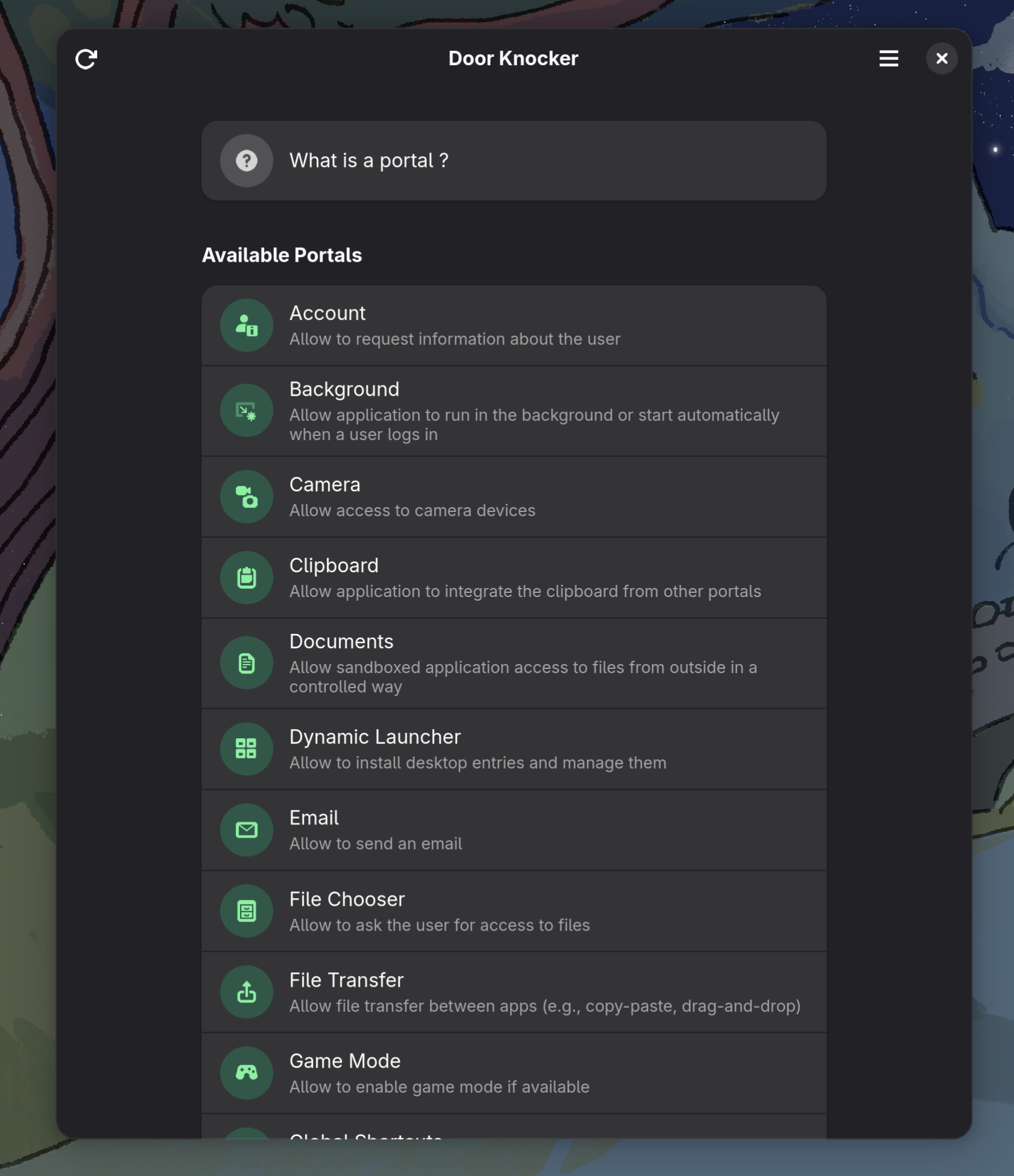

Put simply, a XDG Desktop Portal is an interface that an application - be it inside a sandboxing environment such as Flatpak, or running natively - interacts with the surrounding context to obtain resources, request permissions, and, overall, interact with the system.

As the project description suggests, xdg-desktop-portal exposes a series of D-Bus interfaces, accessible under the standardized name org.freedesktop.portal.Desktop. Those interfaces expose several APIs that regulate the interaction with various resources. Each of those interfaces is a portal.

Portals are especially useful when an application is runs sandboxed, because they act as a portal to interact with something that is inside the sandbox. It makes intuitive sense: in Portal, you use portals to break out of undesirable situations. On the Linux desktop, you use them to access something that it outside your sandboxed context.

However, it is crucial to understand that portals are not exclusive to sandboxed environments. They expose standardized APIs, which means that you, as a developer, must not worry about the differences between desktop environments, windowing systems, or how the application is executed. If you use Portals, you can rest assured: your application will just work, everywhere, however your users have decided to install it. And, if you need to ensure it will run predictably on any distro, regardless of what versions of your dependencies an installation bundles, you add Flatpak to the mix.

Different portals expose different resources, and each desktop environment is tasked with implementing each portal. The challenge here is that, for the more niche portals, it is not guaranteed that every desktop environment has a working implementation for that portal. Sadly, this is as good as it gets: if a desktop environment does not support XYZ at all, then XYZ will not work on that DE.

There are portals for several use cases, and more keep getting added! For example, the Camera portal regulates access to your webcam, the Documents portal allows a sandboxed application to access a single file of your choosing without needing to have access to an entire directory, the File Chooser portal will use the correct file picker dialog for your current desktop environment, and the Game Mode portal allows a game to let your DE know when it is running, typically suspending non-essential background tasks (like automatic updates) while the game is running, to free avoid slowing down the game by allocating resources.

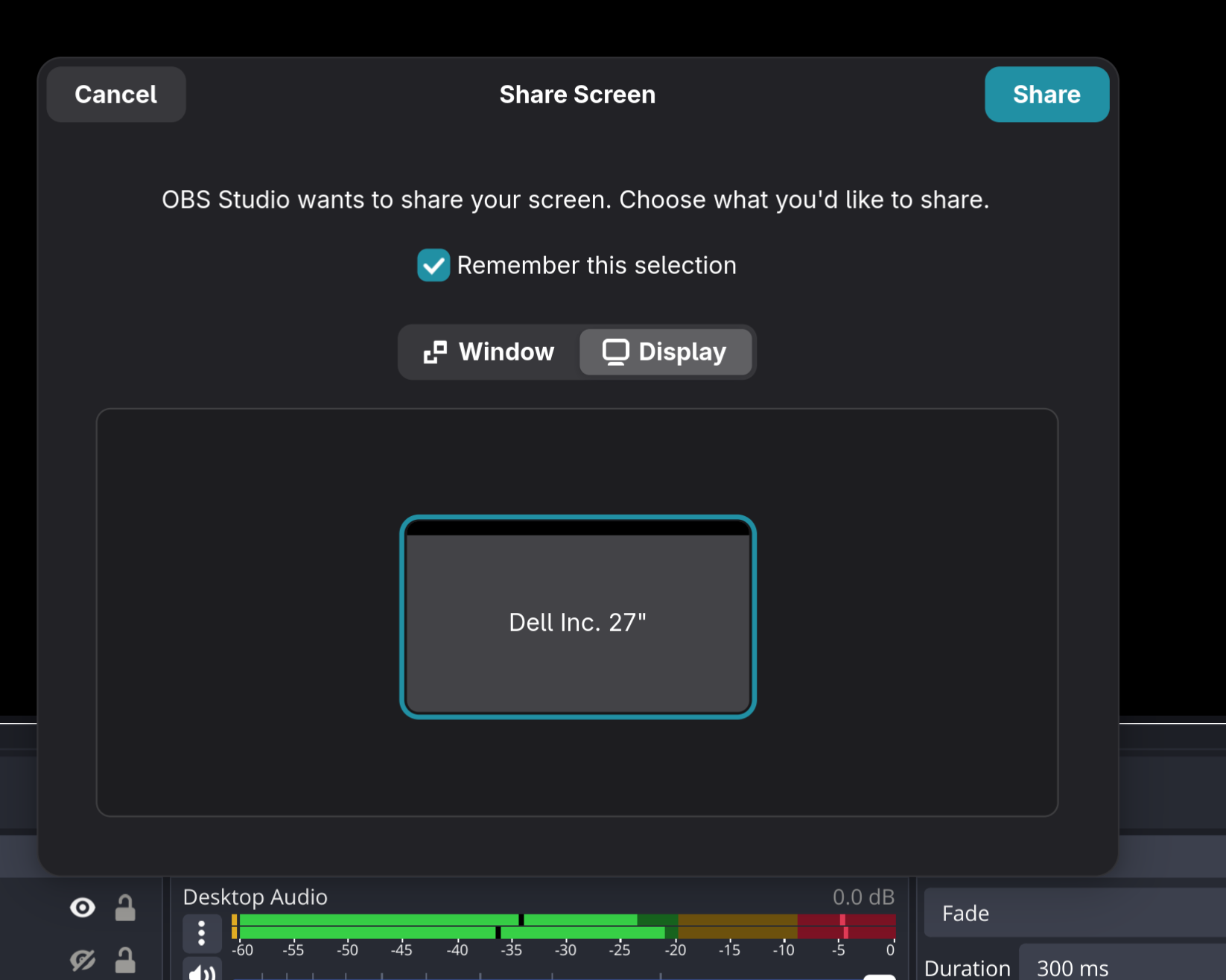

Portals also allow implementing a permission system for the most crucial permissions. For example, the dialog you get when you try to share or record your screen with something like OBS or Discord is part of the Screencast portal!

Wrapping up

Freedesktop Portals are the unsung hero of the Linux desktop, and this beautiful plurality of desktop environments and packaging formats wouldn't exist without them.

Portals are evolving, too. Expect new portals to expose even more functionality, coming to a box near you!