Table of Contents

A few months ago, I discovered a project called "EU OS." It seemed interesting, so I added it to the list of article ideas and quickly forgot about it. A month later, it somehow reached every news and YouTube homepage. And yet, I believe most of them completely missed the point; let's discuss that.

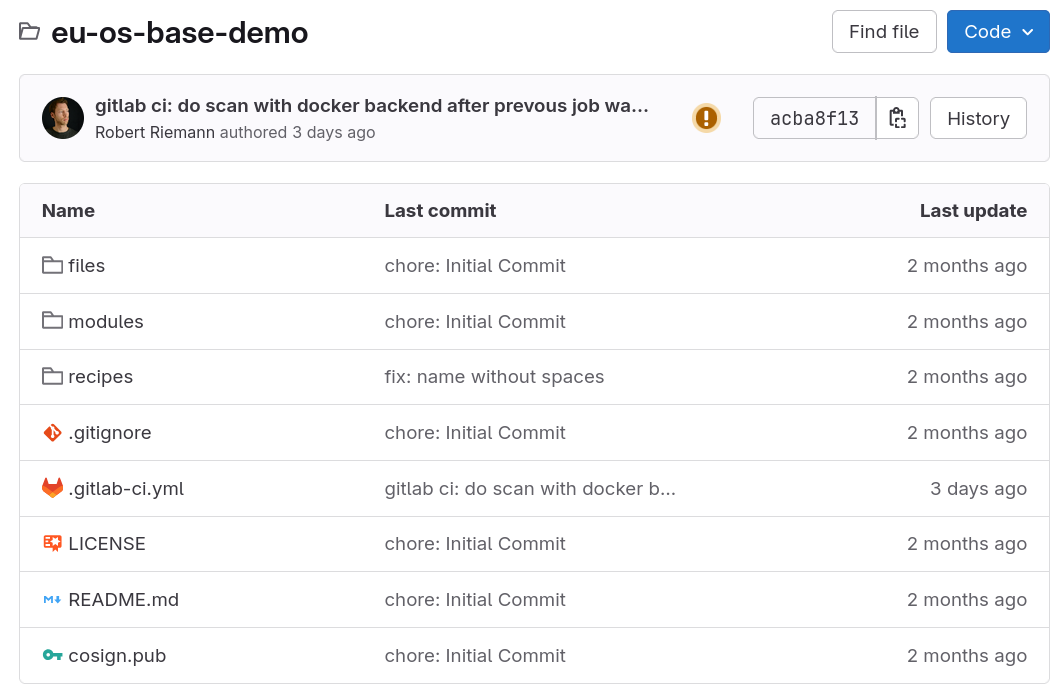

EU OS is a proof-of-concept operating system based on Fedora and built by developer Robert Riemann, head of the Digital Transformation sector in the Technology & Privacy Unit at the European Data Protection Supervisor.

To be clear, EU OS is the free-time project of Robert, and it's not embraced by EU institutions in any way; currently, it's a one-man project, though it's quite a skilled "one-man".

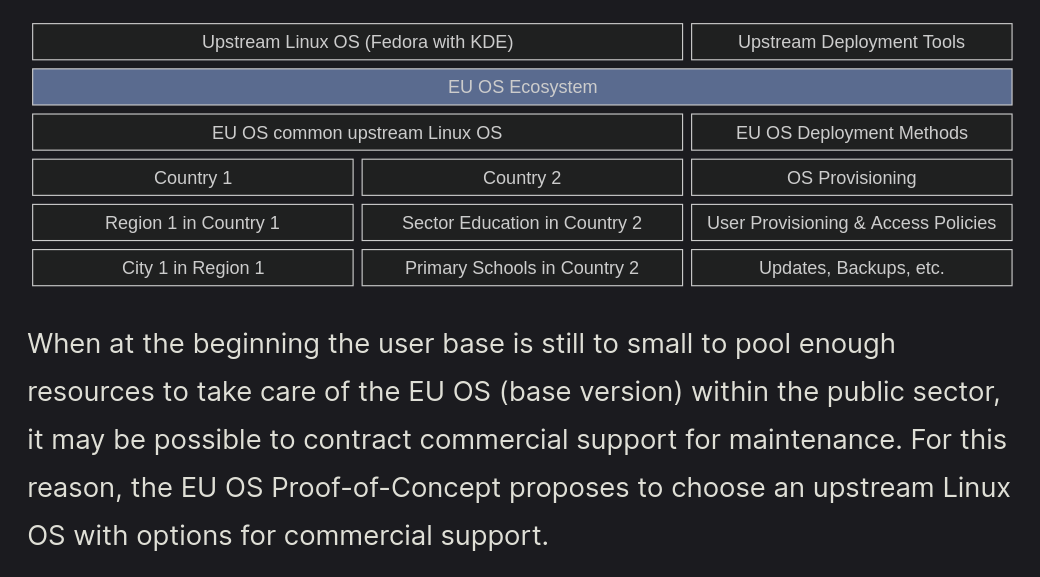

The end goal is to transition the public European infrastructure towards an open-source, Linux operating system. This brings some extra deployment requirements which EU OS has to address, such as the ability to provide an easy way to adapt to different regions and sectors, and ease of management for system administrators on a large scale.

As such, EU OS is described as "not meant for home users, but for system administrators who want to deploy automatically Linux to many corporate computers/laptops". EU OS wants to "propose a common Linux OS based on bootable container technology [...] and a common method to manage users and their data".

Let's immediately place EU OS within a larger context. The broader initiative is "Public money, public code", which aims to make all software created through taxpayers' money as released as Free Software (and, more generally, to push for the usage of open-source within public institutions).

There have been a few local successes of this initiative. The most notable example was the city of Munich, which had migrated more than 80% of all of its desktops to a Linux derivative called LiMux. However, the move has been reverted, and the city has returned to using Microsoft Windows. Nonetheless, LiMux has been the first Linux desktop certified for industry use by the German Technical Inspection Association, and had managed to save more than 10 million euros.

On an international level, we have three examples: Astra Linux, widely deployed in the Russian Federation, Kylin and Neokylin, with a 90% market share in the Chinese government sector, and Nova Linux, used within the Cuban public sector. You might notice some connection between these, though we will get back to it later on.

Nonetheless, Robert points out that these examples leave "no doubt on the feasibility of large-scale Linux deployments in the public sector. It is only a matter of political support, priority, and funding".

So, why isn't there political support for this? Especially considering the clear benefits that this migration would bring; we're talking about tax savings, since you wouldn't have to pay for licences of commercial products. You'd also avoid software suppliers and vendor lock-in: with Windows, you're entirely in Microsoft's hands regarding support of a certain operating system, and - even worse - the type of hardware you need to run the supported versions of Windows. And, of course, open standards foster innovation, they take fewer IT administrator resources, and benefit from the worldwide free software community.

Is all of this what brought China and Russia to ditch Windows in favor of Linux? If I had to bet, there's some other reason that is better explained through our favorite topic ever, politics.

Obviously, China/Russia and the US are not what I'd call friendly allies. Thus, these countries probably started internal efforts to make their governmental sections independent from closed-source US-based software, such as Windows. By pivoting to Linux, they're able to check for backdoors in the operating system and develop their own flavor, which they control entirely.

On the other hand, the EU has been considered an ally to the US for years now; however, thanks to the latest US administration, this statement is beginning to be a bit more doubtful. Thus, the timing of this EU OS initiative is most likely not as random. Indeed, I also agree that the current political climate makes the usage of locked-down proprietary software from the US somewhat risky, and it might be time to consider sovereign options.

However, a lot of discussion has been raised on exactly what we should mean by "sovereign options". Many, such as Brodie Robertson, have criticised EU OS for their usage of Fedora, which is an international project but has ties with the US company RedHat.

The Register even decides to call Fedora an "American distro", which – is not something I would say, like, ever. Again, Fedora is not developed by or in any specific country, and the team is international; it is however true that many core (code, legal, …) contributors are also RedHat employees.

However, applying this sort of thinking gets complex quickly. As an example, Brodie also mentions that EU OS uses the KDE Plasma desktop, and he says he's fine with that since the KDE e.V. is based in Germany (and, thus, it's "fair to say that KDE is German").

First of all: no, it's not fair to say that. KDE is an international project that's not developed by or in any specific country. The KDE e.V. non-profit is, yes, German, but it's a different entity compared to KDE and products such as Plasma are not products made by the KDE e.V.. This might seem stupid to say, but it's relevant both legally (as in, KDE products are not legally developed in Germany), and practically (as in, the most common country of origin of KDE developers is not Germany).

And, if you want to go further, I want to point out that many core KDE contributors, such as myself, are employed by Tech Paladin, which is a US country yet again. Even worse, the primary owner of Tech Paladin, Nate Graham, is also on the board of the KDE e.V.. Thus, by the same logic as Fedora, KDE also has direct and strong ties with an American company. Brodie should be well aware of this, since he has just interviewed Nate – I haven't watched the video yet, I'm really sorry, I promise I will.

And we could go on: sure, Linux is an international project, but it has direct ties and gets funding from the Linux Foundation, which is US-based. Mozilla Firefox is developed by a for-profit American company. Even OS components like PipeWire have direct ties to, again, RedHat. Thus, if our criteria for sovereign software is "has direct ties with US companies" then let's just give up, there's nothing we can do.

However, I believe that to be flawed logic. Let's instead talk more practically: the issues with using American software is security (as in, they might contain government backdoors) and independence (as in, future decisions by American companies might have a direct negative impact on EU institutions using their software). These are the main risks we want to mitigate.

Evidently, by using FOSS software, we're safe on the security part of this. Since development happens publicly, the US government cannot go to, e.g. RedHad and kindly ask them to add a backdoor in – they wouldn't be able to, or it would at least be orders of magnitude harder compared to Windows, since you'd have to do it publicly (thus, fooling the entire world).

Let's talk indpendence. FOSS software also provides a good layer of protection here: if RedHat decides to try to kill Fedora tomorrow, they wouldn't be able to; the project would get forked and the existing community would continue development, though certainly at a slower pace. If necessary, the EU could also create its forks of the software it relies on, and fund their development. This means that open-source here provides an exit strategy in case something goes wrong, which is all we need.

I think that the strength of my arguments here is proven by the fact that both AstraLinux and Kylin are entirely based on Linux distributions and FOSS software that's developed around the world, US included. They have strong reasons to want independence, and yet they're fine with using FOSS software even when it has ties to other countries.

Robert also agrees with me, because he's smart. He says,

EU OS shall not confound sovereignty and protectionism. There is no problem per se in relying on international FOSS components and often times it is in practice unavoidable.

However, EU OS promotes to maintain strict control on business data and telemetry data. This includes the free choice where to store such data (on-premise or cloud of choice). Furthermore, the availability of know-how for a given FOSS component within the EU shall be considered.

Also, I feel like we're getting sidetracked on this sovereignty part of the discussion, whereas the point of EU OS was to be a proof-of-concept that you can deploy Linux desktops at a large scale within the EU, which is a different goal entirely.

That said, do allow me to briefly make fun of a couple of news articles about this.

I've already criticized The Register's "American distro", but I believe that the Linux Journal also seriously missed the point by publishing "EU OS: A Bold Step Toward Digital Soverignty for Europe".

A… bold step? Are we really calling an unofficial one-man project… a bold step towards digital sovereignty? It would be a bold step if the EU embraced this, but they did not so far.

The article by It's FOSS is good, but I love the very first comment: There won't be privacy and such if an American is corporate behind it, in America you are forced to let the government have access to your software security or you go under. Which not only is just straight-up false, but also misses the point entirely that RedHat doesn't own Fedora nor can they hide backdoors in it.

Let's move on, though.

The EU OS project has gained the attention of OpenSUSE too; they recently released an article offering some criticism of the project.

They say,

The current Fedora+KDE direction is mature, but relying on one distro and one desktop environment introduces avoidable risks. Instead, it would be wise for all governmnets to embrace alternatives like Aeon with GNOME, alongside another immutable Plasma-based choice of Kalpa. Why? Security. Different distributions and desktops reduce the risk of a single point of failure. If vulnerabilities emerge, they won’t simultaneously impact every system.

This is an understandable position: by only offering one distribution and one desktop, you are more exposed to events related to those projects specifically.

However, I believe that EU OS mostly picked Fedora and KDE as placeholders, as the real proof-of-concept is about the deployment of the systems.

I do want to bring forward one criticism of my own, though, and I accept that I might be incorrect. Are we sure that we're not just talking about a name, here?

If we go check the project itself, the only repository is almost devoid of any code. Almost all of the folders that I'm currently showing on screen are empty.

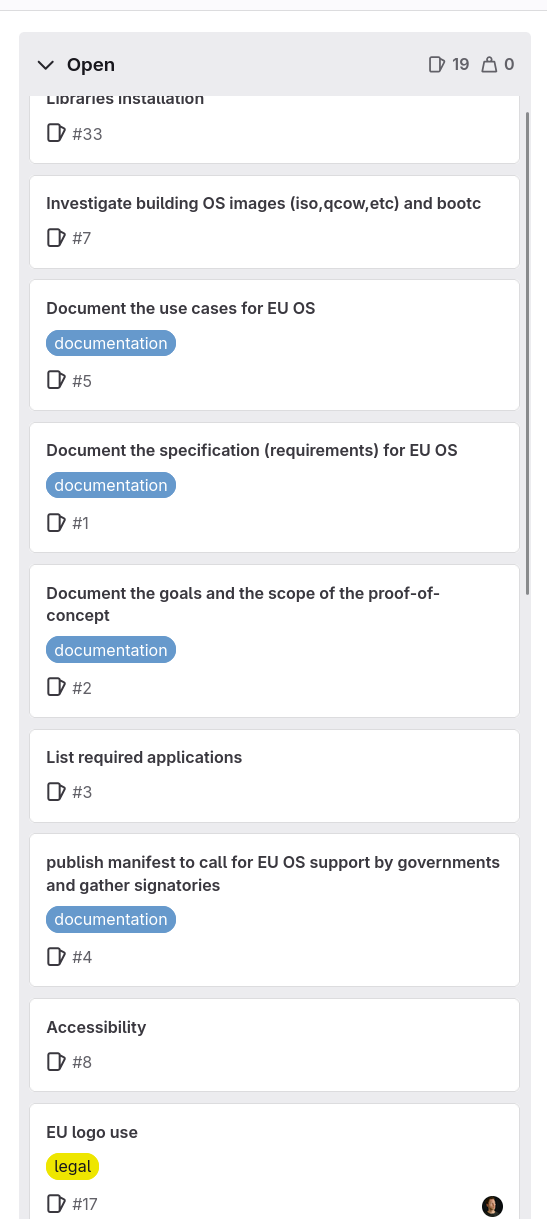

If we go ahead and see future planned tasks, we have things like: document use cases for EU OS, document requirements for EU OS, document the goals and the scope of the proof-of-concept, list required applications, publish manifest to call for EU OS support by governments, add EU OS branding, and more.

All of this is necessary work, but it makes me think that this project is well within the concept phase where it's not even sure what it wants to be, or how. There's nothing concrete about this.

And, again, this is a one-man project, and none of this is backed by any EU institution. I might be wrong, but to the best of my knowledge, right now EU OS is an idea of one person, and I do not understand why are we talking about it.

Or, I think I do: it's not about the project itself. Rather, EU OS is an excuse to discuss an abstract concept that does not yet exist, but that applies to the current times: the idea of an EU independent operating system. I think this is why everyone seems interested in the sovereignty part of EU OS (even though the large scale public sector distribution is the key part): right now, we want to discuss EU sovereignty, we need to discuss EU sovereignty; and, to do so, we've taken what would've otherwise been a negligible topic, and all started talking about it.

Robert, by the way, feel free to reach out to tell me that I'm wrong about this, and that EU OS is much more important than I think it is; I'm ready to admit that I may be missing something.

Nonetheless, let's try to go further. What is the Eurepean Union doing to embrace open-source and digital sovereignty? This video is long already, but let's try to provide a rough overview.

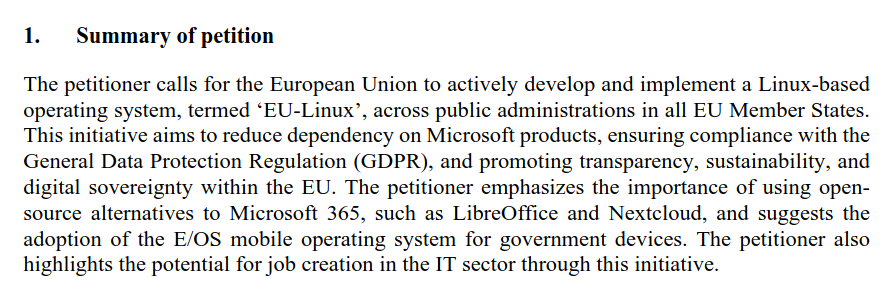

We can do so thanks to a petition that has been presented to the European Commission. This petition asked the EU to develop and implement a Linux-based operating system called "EU Linux" across public administrations in all EU member states. Again, benefits are listed: independence from Microsoft, compliance with GDPR, transparency, and so on.

Before you get excited, the response by the Commission is "there is currently no formal project to establish an EU Linux", understandably so (these are not the type of things that are achieved through Commission petitions; they're more similar to information requests).

Nonetheless, the response also highlights all of the current efforts by the EU in regard to open-source software in the public administration.

Firstly, there's legislation. I've covered many of them, such as the Digital Markets Act, but more recently we've seen the Interoperable Europe Act "foster seamless cooperation between digital systems, prioritizing the use of open source and open standards".

There are also programs such as the Digital Europe Programme, CEF Telecom, and the ISA2 interoperability programmes, to "support the EU's digital transformation through open source solutions". Horizon Europe also funds a "wide range of projects that involve development and use of open source software and hardware", with its Next Generation Internet having invested "more than EUR 140M in over 1000 community-led open source projects".

There's also a body called the Open Source Observatory who has been tracking "news, reports, and case studies, demonstrating the growing adoption of open source across the EU. This includes recent national governments' efforts to develop and implement open source alternatives to proprietary office collaboration suites, closely aligned with the petitioner’s intention".

The Commission also uses open-source software internally; as an example, the majority of their websites are built and Drupal, and they mostly use Linux in data centers.

There's also a Commission Open Source Strategy which "encourages the use of open source within the organization, promotes collaboration through code.europa.eu, and paves the way for more sustainable and transparent digital infrastructures. The Commission organizes bug bounties and hackatons on open source solutions that are of interest, such as Nextcloud, and supports open source adoption in critical areas".

Now, all of this is still miles away from Linux being the standard operating system in the government sector; and, honestly, Linux itself needs to improve for corporate usage before we get there. This is why I absolutely embrace projects like EU OS, don't get me wrong! However, I feel like this round of news got a bit too excited and misunderstood the current goal and size of the project.